An email sent to me today goes,<br /> <br />Sometimes A Game Means Much More Than The Score <br />By JOHN FEINSTEIN, Christmas 2004 <br />One of the questions I am frequently asked is: "If you could only go to one event in sports every year, which one would it be?" <br />Most people expect my answer to be The Final Four or The Masters or perhaps Wimbledon or The World Series. I love each of those events and consider myself fortunate to have covered them often through the years. But the answer to the question is simple: Army-Navy. <br /><br />There's just nothing like the Army-Navy football game. Not because of the quality of the football game, but because of the quality of the people playing the football game. And because of the quality of the people who have played in the game in the past. Saturday, when Army and Navy play for the 105th time, the day will be special. Not because Navy is 8-2 and going to a bowl game for a second straight season. Not because Army is 2-8 but well on the way back to respectability under the leadership of Bobby Ross. Not because Navy fullback Kyle Eckel is a good enough player that pro scouts say he could be a third or fourth round draft pick this spring. <br />That's all well and good. It is also well and good that, regardless of the size and speed of the playersor lack thereofthe game will be played very hard, with great intensity and emotion and a minimum of trash-talking. The nature of Army-Navy is best summed up by a brief moment three years ago when President Bush conducted the coin toss just 10 weeks after the tragedies of 9-11. When he tossed the coin into the air, Navy captain Ed Malinowski made the call on behalf of his team:<br />"Heads SIR!" he said, loud and clear for everyone in the packed stadium to hear. We all smiled at that moment because only at Army-Navy would you hear a future marine tell the President of the United States, "Heads SIR!" during the coin toss.<br />Saturday, when the coin is tossed, Malinowski will be in Iraq. So will a number of players who were on the field that day along with many others who have played in Army-Navy games in the recent past. They will be on the minds of all of us in the stadium throughout the day. Scott Zellem, Ron Winchester, J.P. Blecksmith and Kevin Norman will also be on our minds. All played football at Army and Navy. All graduated and went overseas to fight for their country. In the last year, all died for their country. They aren't the first and, sadly, they won't be the last. When Norman died last spring, Jim Cantelupe, his roommate at West Point, talked about what he and all of those who attend the academies know and understand about life in the military.<br />"You never want to think you're going to die overseas," he said. "But you know that it's possible. Every day that you're there, you're preparing for the possibility that you may have to fight for your country. You don't want to have to do it, but you have to be ready, willing and able to do it. We all are. We know that's why we're there." <br />If you are ready, willing and able to fight for your country, then you must accept the possibility that you may die for your country. When Pat Tillman, the one-time Arizona Cardinals defensive back died in Afghanistan last spring, much was madeproperlyof the fact that he died a hero because he died fighting for his country. But what made Pat Tillman a hero wasn't the fact that he died for his country, it was that he was WILLING to die for his country. <br />Every player on the field Saturday will be like Pat Tillman: willing to die for his country. Sure, Pat Tillman gave up a lot of money and glory when he left the NFL to volunteer for the Army. The players at Army and Navy may not be as gifted or as wealthy as Tillman was, but they made a decision similar to his: they are all good enough students that they could have gotten into almost any college; almost all are good enough players that they could have gotten scholarships at Division 1-AA schools (at least). All could have left Army or Navy after two years, no harm, no foul and gone to school someplace else. All elected to stay, knowingespecially nowthat they might very well find themselves in harm's way soon after graduation. <br />Zellem graduated from Navy in 1991. He was long past his five year commitment when he died earlier this year. The same was true for Norman, Army class of 1996, who steered his plummeting airplane away from a populated area and crashed into a bridge so only he and his co-pilot would die. Winchester and Blecksmith were younger, but understoodand embracedthe risks they faced. <br />This week, the football players at Notre Dame faced a crisis: their coach was fired quite suddenly. Should they agree to play in The Insight.com bowl? The players at Auburn may face the unfairness of finishing a season undefeated and yet not being allowed to compete for the national championship. The players at Rutgers just went through a 12th straight losing season. <br />Adversity? Sure. But not exactly adversity that matches what Zellem, Winchester, Blecksmith, Norman and their families have faced this year. Not exactly the adversity that many of the players who will play in Philadelphia on Saturday may be facing a few months from now. <br />Almost every college football team likes to post some kind of inspirational message over the door of its locker room. Things like, "Winners never quit and quitters never win." As the players exit the locker room, they all reach up and touch the sign to remind themselves to try to live up to the words. More often than not, the message changes when the coach changes. But at Army, for as long as anyone can remember, the sign over the locker room door has been the same: "I lay me down to bleed awhile but I will rise again to fight." <br />Think about those words. In many ways they sum up exactly what our countryregardless of how one feels about the war in Iraqhas done since 9-11. They also explain perfectly the mentality of those who play football at Army and Navy. Knock me down and I will get up. Knock me out and I will still get up. Kill me and others will rise to take my place. I may lose a battle, but I will never surrender.<br />Perhaps that's all just too corny to even ponder in a sports world dominated today by Ron Artest and on-field brawls in so-called, "rivalry," games and multi-millionaire athletes wrestling for money with billionaire owners. But it is what Army and Navy has always been about and always will be about. You see, I want to be at Army-Navy on Saturday because Tyson Stahl will be there. Tyson Stahl is a Navy senior. His older brother Hoot, also a Navy football player, is currently on his second tour of duty in Iraq. A year ago, Navy assistant coach Jeff Monkon received an American flag from a friend, who happened to be an ARMY officer stationed in Baghdad. The flag had flown over the Baghdad Airport shortly after the American takeover of the city. Monkon's friend wondered if the Navy football team might have some use for the flag. <br />It did. Prior to each game that flag, carried by Tyson Stahl has led the Navy team onto the field. Thinking about his brother as he carries the flag, Tyson Stahl says that each time he carries it with his teammates behind him, "It is the proudest moment of my life." <br />I wouldn't miss seeing that moment in a stadium filled with people who feel as I do; people who will be thinking of Hoot Stahl and Ed Malinowski and Scott Zellem and Ron Winchester and J.P. Blecksmith and Kevin Norman, for anything else but sports. <br />Not this year. Not any year

- Shop

-

Main Menu Find The Right Fit

-

-

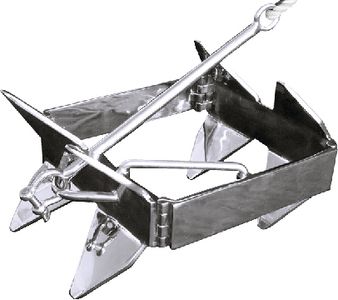

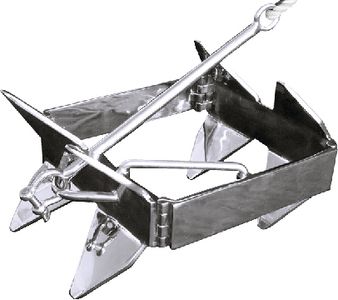

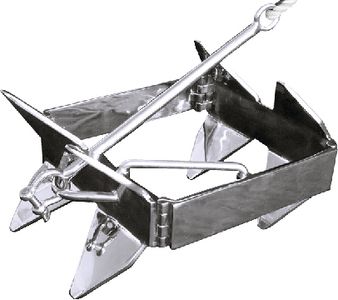

Slide Anchor Box Anchors Shop Now

-

Back Fishing

-

View All

- Fishing Rods

- Fishing Reels

- Fishing Rod & Reel Combos

- Fishing Tools & Tackle Boxes

- Fishing Line

- Fly Fishing

- Fishing Bait & Fishing Lures

- Fishing Rod Holders & Storage Racks

- Fish Finders, Sounders & Sonar

- Trolling Motors

- Fishing Nets

- Fishing Downriggers & Acessories

- Fishing Outriggers & Acessories

- Fishing Kayaks

- Fish Cleaning Tables

-

-

Minn Kota Riptide Terrova 80 Trolling Motor w/i-Pilot & Bluetooth Shop Trolling Motors

-

SportsStuff Great Big Marble Shop Tubes

-

Big Jon Honda 5hp Outboard Shop Outboards

-

Lexington High Back Reclining Helm Seat Shop Helm Seats

-

Kuuma Stow n Go BBQ Shop Now

-

Slide Anchor Box Anchors Shop Now

-

Back Electrical

-

View All

- Boat Wiring & Cable

- Marine Batteries & Accessories

- Marine DC Power Plugs & Sockets

- Marine Electrical Meters

- Boat Lights

- Marine Electrical Panels & Circuit Breakers

- Power Packs & Jump Starters

- Marine Solar Power Accessories

- Marine Electrical Terminals

- Marine Fuse Blocks & Terminal Blocks

- Marine Switches

- Shore Power & AC Distribution

-

-

ProMariner ProNautic Battery Charger Shop Marine Battery Chargers

-

Lowrance Hook2-4 GPS Bullet Skimmer Shop GPS Chartplotter and Fish Finder Combo

-

Boston Whaler, 1972-1993, Boat Gel Coat - Spectrum Color Find your boats Gel Coat Match

-

Rule 1500 GPH Automatic Bilge Pump Shop Bilge Pumps

-

Back Trailering

-

SeaSense Trailer Winch Shop Trailer Winches

-

Seadog Stainless Steel Cup Holder Shop Drink Holders

-

Slide Anchor Box Anchors Shop Now

-

- Boats for Sale

- Community

-